There is a question that sits at the very heart of the human experience—a quiet hum beneath the noise of our lives whispered for millennia by thinkers in candle-lit rooms and dreamers staring at the stars: What is real?

In 1999, a film took this ancient question and wrapped it in black leather, dark sunglasses, and slow-motion action. On the surface, The Matrix was a revolution in cinema, but its true revolution was one of ideas. It was more than just a movie; it was a mirror, a sermon delivered in code, and a warning about a future that might already be here. For over two decades, we have been willingly falling into its depths, trying to decipher its meaning, because the prison it described wasn’t made of steel and concrete. It was built from perception itself.

This is a world built on doubt, faith, and the fragile line between them—a world where nothing is certain except the choice you must make: Red pill, or blue.

In this article, we’ll peel back the layers of CGI and bullet-time to explore the profound philosophical ideas that form the source code of The Matrix, from ancient Greece to modern France.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave: The First Step Out

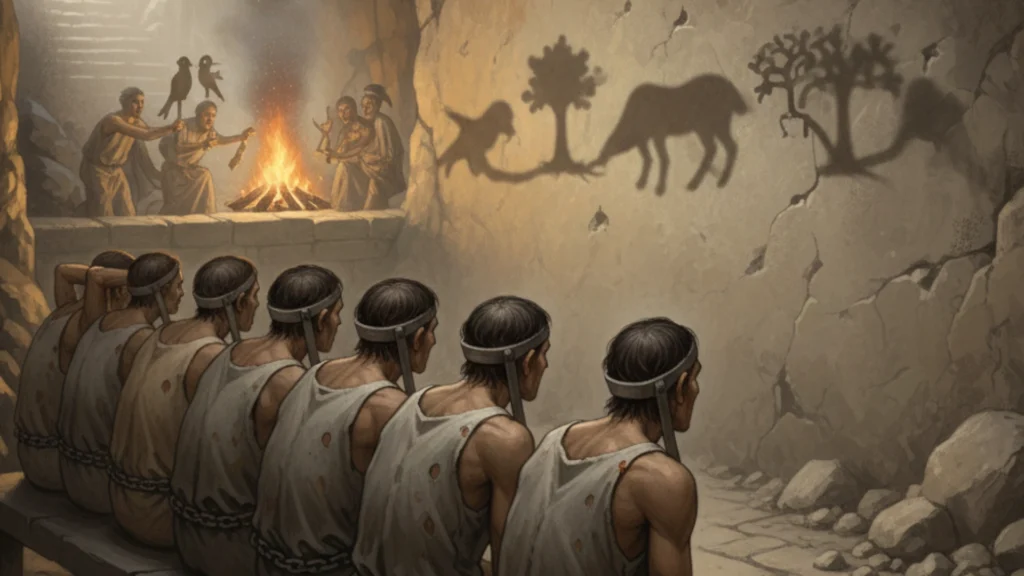

The foundation of The Matrix is an idea so old, its first telling was by firelight in ancient Greece. To understand the film, one must first understand Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

Plato asked us to imagine a group of prisoners, chained since birth in a deep, dark cave, unable to move their heads. All they can see is the wall in front of them. Behind them, a fire burns, and between the fire and the prisoners, people carry objects that cast flickering shadows on the wall. For the prisoners, these shadows are not imitations; they are the only reality they have ever known.

Now, imagine one prisoner is set free. He is forced to turn and see the fire and the objects. The light is painful and confusing. He is then dragged out of the cave into the world above, where the sunlight is blinding. But as his eyes adjust, he sees true reality for the first time: trees, stars, and the sun itself. He understands that the shadows were merely faint copies of this true world. This is the torment, and the triumph, of enlightenment.

The film reconstructs this allegory in circuits and code. The Matrix is the cave—a neural-interactive simulation that has imprisoned humanity. The sleeping billions, their bodies in pods, are the prisoners. And Neo… is the one set free. Morpheus, the philosopher who unchains him, asks why his eyes hurt. “Because you’ve never used them before.” Neo has been blinded by the light of the truth.

The allegory is tragically completed when the freed prisoner must return to the cave, where the others would not believe him, calling him insane for threatening their reality. We see this perfectly in the character of Cypher. He has seen the truth, but found it too harsh. He makes a deal to be reinserted into the cave, to forget the truth in exchange for the comfort of the shadow-play—for the taste of a steak that he knows isn’t real. He is the prisoner who demands to be put back in his chains.

Descartes’ Demon in the Machine

What if the prison wasn’t a neutral space? What if the illusion was an act of aggression—a grand lie fed to you by a malicious power?

Centuries before cinema, the philosopher René Descartes tortured himself with this very thought. To build a system of knowledge on a foundation of absolute certainty, he began the “Method of Doubt,” deciding to doubt everything he believed to see if anything remained. He could doubt his memories, his senses, and even the existence of his own body.

He took it a step further with a thought experiment: the Evil Demon. Descartes imagined that a supremely powerful and malignant being was dedicating all its energy to deceiving him, projecting all his sensory experiences directly into his mind. Since he could not prove this demon didn’t exist, he concluded he could not truly trust his senses.

In The Matrix, this demon is not a hypothetical. It is the Machines. The AI that defeated humanity and turned them into batteries is the literal manifestation of Descartes’ evil demon, creating a seamless illusion to keep their power source docile. The Agents are the demon’s enforcers, programs designed to eliminate any person who begins to question the deception.

Yet, Descartes found one, single, unshakable truth in his sea of doubt. Even if a demon was deceiving him, there had to be an “I” that was being deceived. The act of doubting proved the existence of a doubter. His famous conclusion: Cogito, ergo sum. “I think, therefore I am.”

This is the most terrifying rule of the Matrix. The world is a fiction, but your mind is real. And because your mind believes it, the consequences—the pain, the death—are real. The demon’s lie has power over the physical body.

Baudrillard’s Simulacra: Welcome to the Desert of the Real

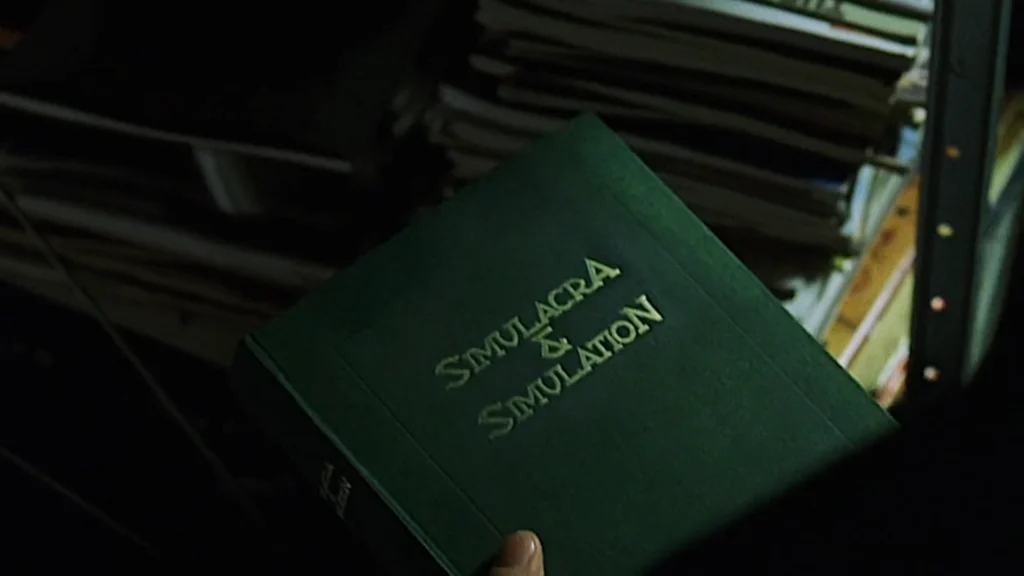

Early in the film, Neo pulls a disc from a hollowed-out copy of “Simulacra and Simulation” by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. This is no accident; it is the film’s most direct philosophical citation.

Baudrillard argued that modern society is so saturated with copies, symbols, and media that we have lost the ability to distinguish between reality and simulation. He described a world where the image no longer reflects reality but masks its absence entirely. This leads to the creation of a simulacrum: a copy without an original. The world it creates is what Baudrillard called “the hyperreal,” a state where the simulation becomes more real and more desirable than reality itself.

The Matrix is the ultimate simulacrum. It is a perfect simulation of the world at the peak of human civilization, a world that was destroyed and no longer exists. It is a copy without an original. When Morpheus frees Neo, he directly quotes Baudrillard, gesturing to the ruined world and saying, “Welcome to the desert of the real.”

This is perhaps the film’s most uncomfortable idea because the real is a desolate wasteland. The simulation, by contrast, is full of comfort, sensation, and flavor. The copy has become superior to the original. Interestingly, Baudrillard himself felt the film missed his point. He argued that we are already in the simulation. There is no red pill to take, no “desert of the real” to wake up to, because we have already submerged ourselves so deeply in simulacra that there’s no outside left. In a way, he believed the film was too optimistic.

An Existential Choice: Knowing the Path vs. Walking the Path

If reality is suspect, what can we hold on to? The film offers an answer that echoes the school of Existentialism, whose core tenet is “existence precedes essence.” This means you are not born with a pre-defined purpose. You are born, you exist, and then, through your actions and choices, you create your own essence. You define yourself.

Consider the prophecy of The One. The Oracle never tells Neo he is The One. She tells him he has “the gift,” but that he is waiting for something—”Your next life, maybe.” She puts the responsibility squarely back on him. It is not prophecy that makes him The One; it is his choices. The choice to save Morpheus. The choice to face Smith. The choice to believe in himself. This is the meaning behind Morpheus’s most important line: “There’s a difference between knowing the path and walking the path.”

Destiny means nothing until you choose to act. You exist, and then you walk, creating your own path. Even Agent Smith, a program, brushes against this. He longs to be free of the Matrix, a place he finds disgusting. He is a being of pure code who, through his hatred, begins to desire a self-defined existence beyond his programming—a dark mirror of Neo’s own journey of self-creation.

The Final Choice

We are left where we began: in front of a choice between the red pill and the blue pill. It has become a cultural shorthand, but in its original context, it is the ultimate philosophical test.

- The blue pill is Plato’s cave, the comfort of the shadows, the blissful ignorance of the prisoner who refuses to see the light.

- The red pill is Descartes’ Method of Doubt, the terrifying but necessary act of questioning everything to find a single, unshakeable truth.

- The blue pill is Baudrillard’s hyperreality, the acceptance that the delicious, fake steak is better than the cold, real gruel.

- The red pill is the existentialist mandate, the understanding that purpose is not given, but created through action.

The Matrix did more than entertain. It took a syllabus worth of philosophy and made it visceral, leaving us with one final, unspoken question that hangs in the air long after the credits roll… Which pill did we choose today?

We still live in the Matrix,. because we are still looking for both the cause of the problem and the solution everywhere outside,. And actually it is always only in us. our both the cause of everything and the solution! ,. let’s remember that at the beginning of everything was the WORD. it is information in DNA and instinct that we inherited from our ancestors. so be careful what information and words you take in and give out !,. THE WORD IS ALIVE AT ALL TIMES he is with us, he is in us and around us! ,. And it is the most powerful creative and destructive force as well. And contrary to the general belief that words describe events,. They actually give shape to future events that may happen ! ,. And the WORD is both a tool and a weapon that has always existed and has no equal, the most powerful that ever was and will be ! I can prove that a million times over to the entire planet! ,. with one piece of paper with a short text, you can conquer states and nations or liberate them. break or fix everything,. with one short text on paper! , but that is already a question of ethics and morality and empathy, which should actually be worked on constantly and for the benefit of the whole world !